Writing the Homeland: Nazir Anjum and the Poetics of Resistance

Author: Madiha Ghous

For anyone who grew up in Kashmir between the 1970s and 1990s, or who has been connected in any way with the region’s political life, certain verses are etched into memory — as protests, as graffiti, as the very soundscape of a movement.

Lines like:

"Zulm ko aman, adāvat ko wafā kehte hain,

Kaise nādān hain, sar sar ko sabā kehte hain,

Mere Kashmir jaag, kuch jāh-talab

Ghair ko tere muqaddar ka khudā kehte hain."

and

"Nāra hi nahīñ, īmān hai yeh āzādī ke matwālōñ kā,

Kashmir ka zarra zarra hai Kashmir ke rehne walōñ kā."

These lines have echoed through streets, across rallies, and on the walls of towns — but the name behind them often remained less known to the wider public.

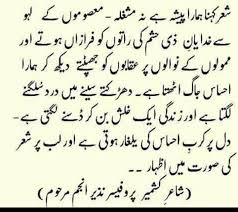

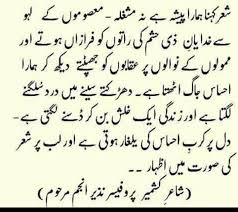

Today’s blog entry is dedicated to the late Professor Nazir Anjum Sahib — remembered with affection and reverence in Azad Kashmiri literary and cultural circles as the "Bulbul-e-Kashmir" (The Nightingale of Kashmir), "Shair-e-Kashmir" (The Poet of Kashmir), and even as the poet laureate of Kashmir.

Nazir Anjum was born on January 1, 1946, in Akalgarh (now Islamgarh), a town in the District of Mirpur, then part of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir (today's Azad Kashmir or the Pakistan Administered Kashmir). He received his early education at the local primary school, completed high school at the Government High School Mirpur, earned his undergraduate degree at Government College Lahore, and went on to pursue a Master’s in Political Science at Punjab University, Lahore.

His professional career was deeply tied to education and the intellectual life of Azad Kashmir. Between 1971 and 1980, he served as a lecturer across various colleges of the region, and from 1980 until his retirement, he served as a Professor of Political Science at the University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir.

While Anjum received select cultural awards during his lifetime, it was the critical recognition from some of Pakistan’s most prominent literary figures — including Habib Jalib, Munir Niazi, Qudratullah Shahab, and Amjad Islam Amjad — that most firmly established his place within the region’s literary and political landscape.

He authored four collections of poetry:

Palak Palak Zanjeer ("Chain After Chain on Every Eyelash"),

Kiran Kiran Tasveer ("A Picture in Every Ray"),

Nafs Nafs Tazeer ("The Imprint of Every Breath"),

Dhuwaan Dhuwaan Tehreer ("Smoky Writings").

These were later compiled into an anthology, a kulliyat titled Qarz-e-Sukhan ("The Debt of Words").

From early on, Nazir Anjum emerged as one of the strongest progressive voices from Azad Kashmir, writing in the leftist tradition that spoke openly against oppression, inequality, and exploitation. While his poetry often carried a romantic and lyrical aesthetic, it was never apolitical: beneath its beauty lay a radical political charge. His work stared directly at the socio-political realities of Kashmir — challenging structures of power, interrogating betrayals, and calling for resistance.

Love of homeland — not just in an abstract sense, but love rooted in the very dust, rivers, and stones of Kashmir — was the foremost subject of his work. His poetry insisted that Kashmir belonged to Kashmiris and should be decided by Kashmiris, resisting both internal and external domination. He remained critical of the powers that be, refusing to romanticize either side of the political divide when it came to the aspirations and rights of his people.

Nazir Anjum’s political engagement came at a personal cost. He was detained multiple times, including in camps like Dulaahi Camp, an experience he movingly captured in his poetry. His verses from that period retain a remarkable balance: anger without bitterness, longing without surrender.

In many ways, Nazir Anjum’s poetry shaped the political culture of Azad Kashmir in the 1970s and beyond. He gave voice to the feelings of loss, betrayal, and hope that defined a generation — creating, as it were, the emotional and poetic lexicon of Kashmiri resistance.

~Nazir Anjum’s poetry deserves more than just a passing tribute. This post offers only a glimpse; in future entries, I look forward to sharing closer readings of his poetry — exploring the themes, imagery, and political commitments that defined his voice.~

Stay tuned!

Archives of Resistance: Azad Kashmir in the Long 60s

Author: Madiha Ghous

The construction of the Mangla Dam in Pakistan-administered Kashmir during the 1960s was a pivotal moment — one that reshaped not just the region’s geography but also its political consciousness. Hailed by the Pakistani state as a monumental developmental achievement, the project submerged nearly 400 villages — including the historic city of Old Mirpur — and displaced an estimated 110,000 people.

This event was more than an infrastructural transformation; it became a turning point in how Azad Kashmiris perceived their relationship with Pakistan. The forced displacement and cultural erasure generated widespread disillusionment, leading many to question Pakistan’s proclaimed commitment to the Kashmiri cause.

The Mangla Dam crisis catalyzed a political awakening in Azad Kashmir, galvanizing an emergent resistance movement that eventually converged with broader geopolitical currents to form a transnational Kashmiri liberation struggle.

Through the platform of the Anti-Mangla Dam Front, some of the earliest expressions of a postcolonial Kashmiri nationalism emerged. One of the most potent literary responses to this traumatic experience arose through the Shahr Ashob tradition — a poetic form historically used to lament the destruction of cities.

The 2003 edition of Parbat magazine, dedicated to the history of this period, serves as a crucial archival space where this discourse is preserved and reactivated. Through this platform, works such as Nazir Anjum’s Palak Palak Zanjeer, activist-thinker Raja Najeeb Ahmed’s Aaiena Dar Aaiena, and Waseem Azam’s poetry resurface as vital texts that articulate the affective and political ruptures generated by the dam’s construction.

Literary Mourning: Shahr Ashob and Vernacular Resistance

One of the earliest and most powerful forms of literary resistance emerged through poetry, particularly in the Shahr Ashob tradition. This classical Persian and Urdu poetic form — traditionally used to mourn the devastation of cities during imperial conquest — became a crucial mode of expression for Kashmiri poets grappling with the loss of Mirpur.

But in Azad Kashmir’s case, the destruction was not caused by an invading army, but by a state-led developmental project that submerged a living civilization.

Through these poetic elegies, Mirpur became more than a city; it became a symbol of Kashmiri vulnerability under Pakistani state policies. The mourning expressed in these poems functioned as both an affective and political act — aligning the loss of Mirpur with broader histories of Kashmiri marginalization.

In works like Syed Masoom Zaidi’s "Ik Zinda Tehzeeb Ka Manzar Doob Raha Hai" ("The Site of a Living Civilization is Sinking"), grief becomes an act of political mobilization. The imagery of ijdaad ki qabrein (the graves of ancestors) evokes the dam as an erasure of not just architecture, but of memory itself — an annihilation of centuries of cultural and historical continuity.

Poetry collections such as Nazir Anjum’s Palak Palak Zanjeer and Lahu Lahu Kashmir were written in direct response to the Mangla Dam project. His poems quickly evolved into rallying cries — their verses becoming some of the most popular slogans in the Kashmiri resistance movement across both sides of the Line of Control.

In his poem Mere Kashmir ("My Kashmir"), Nazir Anjum critiques the state's branding of forced displacement as developmental progress. He exposes how political discourse manipulates the language of development to mask dispossession. Oscillating between mourning and militant assertion, his verses invoke shackles (zanjeer) as symbols of political subjugation — not just at the hands of Pakistan, but as part of a larger global structure of imperial violence.

Similarly, Wasim Anwar’s "Jamhoor ki Aawaz" ("The People’s Voice") captures the profound disillusionment that spread through Azad Kashmir after Mangla Dam’s construction. The imagery of ghareeb-ul-watan (wandering exiles) highlights the trauma of forced migration, particularly the dispersal of Mirpuri Kashmiris to Pakistan and the United Kingdom, where they often faced racism, marginalization, and loss of community.

While these literary works mourned the loss of Mirpur, they did not fully reject the idea of Kashmir belonging within Pakistan’s framework. Instead, they challenged the terms of that belonging — demanding dignity, autonomy, and genuine inclusion.

The political awakening sparked by the Mangla Dam was soon reinforced by the Tashkent Declaration of 1966, where Pakistan and India, under Soviet mediation, made territorial compromises after the 1965 war without consulting Kashmiri leadership. This sidelining deepened existing disillusionment.

At the same time, the migration of displaced Kashmiris to the UK globalized the struggle, linking it to Cold War-era anti-imperialist movements. The Kashmiri cause, increasingly, was understood not just as a regional or bilateral dispute, but as part of a broader fight against domination and erasure.

The Mangla Dam crisis stands as a defining moment in Azad Kashmir’s modern political history. What began as a moment of state-led developmental violence evolved into a literary and political movement that challenged Pakistan’s nationalist narratives and reasserted Kashmiri agency.

The poetry, prose, and activism that emerged from this trauma did not merely mourn the lost city of Mirpur — they imagined alternative futures for Kashmir, rooted in autonomy, dignity, and resistance.

Through these cultural and political acts, Azad Kashmir emerges not as a peripheral space, but as a critical site of intellectual and political activity deeply embedded within the broader currents of the Global Cold War.

This post offers only a brief introduction to the literary and political currents that emerged from the Mangla Dam crisis. In the coming weeks, I hope to share more detailed readings of individual poems and activist texts — exploring more closely how memory, mourning, and resistance are woven together in the cultural archive of Azad Kashmir.